Managing defiant behaviors in the classroom can be a challenge for teachers. Behavior management is one of the most crucial aspects of working with young children. Veteran and new teachers alike encounter challenging behaviors every year. It is essential to have a plan in place so that when this happens, you feel prepared. Notice, I didn’t say if but when. The landscape of childhood has changed. This post-pandemic, social media and technology-filled world shows us a different side of behaviors. In education today, teachers commonly manage extreme behaviors that their predecessors only encountered once or twice in their careers. In other words, this ain’t your grandma’s classroom.

These tricky behaviors are not going away. While we can’t plan for every scenario, we can return to the basics and create a foundational understanding of your students’ cognitive functioning. Remember, this advice is not a replacement for speaking with your own team. If you have concerns about a student in your class, please speak with the child’s parent, your school administrator, and the district or school psychologist for help. It is also important to note that the following information represents general experience in my years of education. It does not specifically reflect any current or past students of mine.

Relationships First

Of course, we know that relationships matter when it comes to managing defiant behaviors in the classroom. If you have a child who really believes they are disliked, they will likely act out as a result. As the late Rita Pierson said in her famous TED talk, “Kids don’t learn from someone they don’t like.”

One of my favorite strategies for students who exhibit difficult behavior is to go out of my way to welcome that child each and every day. I make sure they hear me say, “I am so glad you came to school today!” with a big smile on my face and a hug if they’d like. If I can, I do the same when they leave. “I can’t wait to see you again tomorrow!” Simple phrases like this go a long way. It doesn’t matter what type of day is ahead of you with that child or what kind of day you are closing out; make sure your student knows for certain that they are cared for.

It’s not about you… But it is kind of about you.

Here’s the thing. These challenging behaviors are not about you. As a teacher or caregiver, you must stay neutral. Try not to get offended and look at the big picture. I like to whisper to myself to ZOOM OUT when I am in the moment. Keep the bigger picture in mind. A child may be yelling at you or saying hurtful things directly to you, but every big reaction like that is the manifestation of something deeper. (More on this later!) Your job is to maintain the safety of every person in your charge, including yourself. Most of the time that means letting the words and actions directed at you roll off your back and out the door. That said, if you feel there is a serious threat to your safety or the safety of others, call your administrators or a coworker for support immediately.

So, it’s not about you, but it is also a lot about you. That is, your reactions, emotions and feelings, and ability to stay regulated in a heated environment. That is about you. You must be able to access your own coping mechanisms to stay calm. As a professional and as an adult, you must be able to keep yourself in check and not be baited by difficult behaviors. If you expect a young child not to blow up to not throw a fit when things don’t go their way, you should expect at least that much from yourself and demonstrate the ability to do so.

Function of Behavior

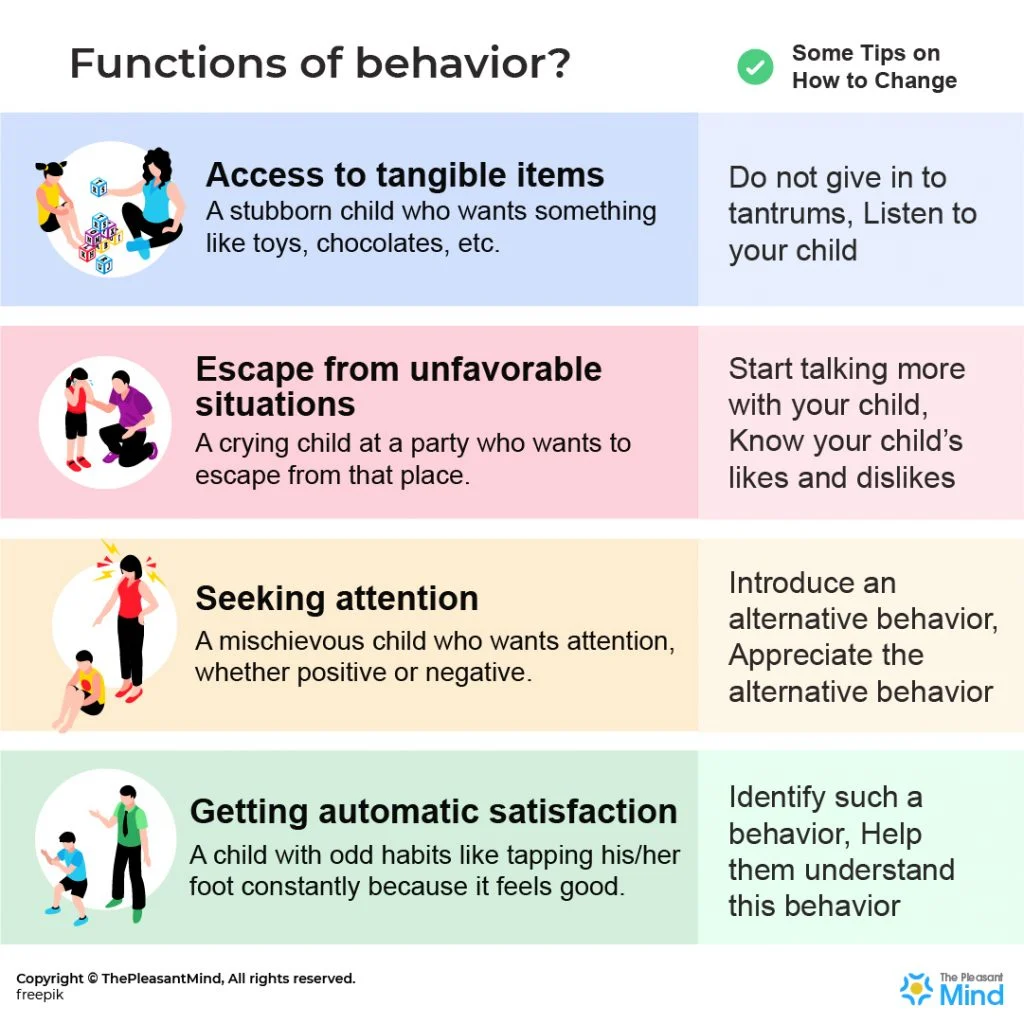

I previously stated that every big reaction is the manifestation of something deeper. Every behavior serves a purpose. Think about whining, for example. Why do children whine? Because they want something and don’t know how to communicate what it is they want. And it’s effective. What is the quickest way to get a child to stop whining? Give them exactly what they are whining about. Let’s take it one step further. According to behavioral psychology, behavior has four functions: escape, access, attention, and sensory. Depending on how deep you dive, there is more to it than that. That will need to be a blog post for another day.

Try to identify the main function of the difficult behaviors in your class. Is the child seeking attention? Are they trying to avoid a nonpreferred activity? Maybe they are trying to gain access somewhere or something? Or could there be sensory factors impeding their ability to integrate? There may be multiple functions throughout the day, hour, or even from moment to moment.

Take elopement, for example. Elopement is defined as any time a person exits further than 3 feet from where they are supposed to be. When your student is running away, are they running because they want attention or to be chased? Or are they running away to escape or avoid because the activity available to them is nonpreferred or too difficult? Are they eloping to access a different area, or is there something else they want to do? Or are they running away because the area they are in is too loud (sensory), and they need a break?

Identifying the function, you can then begin to teach the child to ask for what they need more appropriately. If Bobby is running away to access the bikes he loves, we can help him ask for a 5 minute bike break once his work is finished. If Sally is trying to escape a math center, she may need help with that particular concept and will be happier to comply once she is more confident in her skills. You get the idea. This won’t solve your problem immediately, but it can be a first step to figuring out how to resolve things.

Social Emotional Learning (SEL)

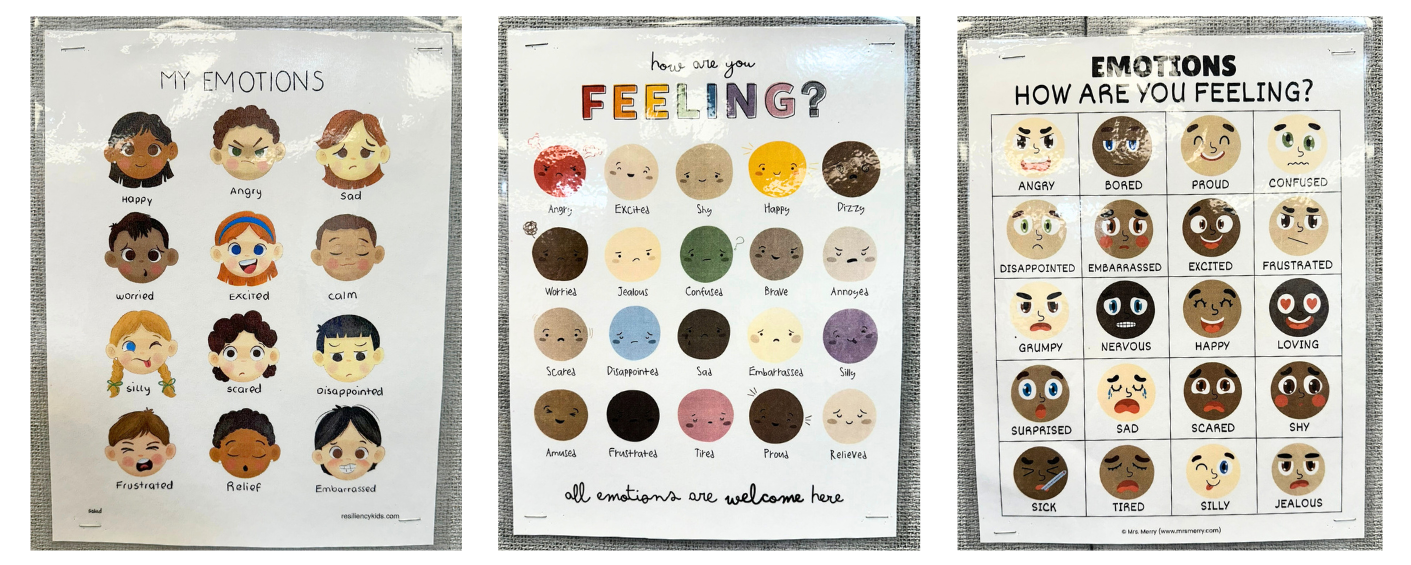

Teaching students the skills they need to be successful in academics is what teachers do. Social skills and emotional intelligence need to be taught in the same way. Set aside time daily or weekly to build competency in this area. It is likely that your school district already has a curriculum that supports this. Some of my favorites are Second Step and Conscious Discipline. If you have not taught your students how to add and subtract, I wouldn’t expect them to perform well on a math test. In the same way, if your students have not been explicitly taught how to identify their emotions, I wouldn’t expect them to be able to tell you that they are feeling angry before they hit someone.

If this feels overwhelming, start with helping your students learn to identify emotions in themselves and others. Work on establishing the vocabulary necessary to communicate their needs and wants. Move toward lessons on identifying triggers and body cues for when they are starting to feel big emotions. Then, learn about coping strategies and ways to manage big feelings.

Zones of Regulation

I absolutely love teaching students about the zones of regulation as a vehicle for SEL lessons. This is another one of those topics that could be an entire blog post of its own, but let’s do a high-level overview. Keep in mind that many of the resources available on this topic may use slightly different language and terminology.

There are four zones: blue, green, yellow, and red. See the graphic above for a closer look. We teach students about each zone, emphasizing that each zone is okay. No zone is a bad zone! Everyone has moments in every zone, but it’s what you do with your time in each zone that counts. Your students must be able to identify the cues to know what zone they are in, which makes the SEL lessons I mentioned earlier so important. After identifying their zone, your students can choose an action associated with how they may be feeling. The beauty here is that students are taking an active role in their own self-regulation instead of being told what to do. Have you ever had someone tell you to calm down or take a few deep breaths? Not helpful… The same goes for our students.

It is important to note that not every child will respond to this right away. We teach that every zone is okay. However, some students may still associate a zone with shame and reject it when prompted. I think exposure to the zones of regulation can still be helpful; just be sure to give it time and offer it up without pressure. I like to prompt my students for a “temperature check” a few times each week and ask students what zone they are in. They don’t need to answer out loud, but they should practice identifying their zone at many different times to help solidify their knowledge and rehearse the skill.

Other Strategies

The rest of these strategies are nothing special; they are just a collection of things I do or say with struggling students and even with my own children at home (ages 3 and 7). Something I like to keep in mind that has helped me so much over the last few years: if you have to yell and scream at a child to get them to do something, they probably don’t have the skills to do that thing independently yet. You may not be yelling and screaming at your students, but the same holds true. If they can’t do it without needing 5-6 (or more) reminders, they probably need help to complete that skill.

My favorite way to combat this is simply by saying, “I’m going to help you now.” Help with the skill, and move on. No lecture is necessary! Other helpful phrases include: “You can do it, or I can do it for you.” “You can do it now, or you can go take a break and then do it.”

- Chunking: If it is clear that your student struggles to complete tasks, then shorten the tasks. Or shorten the time required to attend to the task and come back to complete it later on.

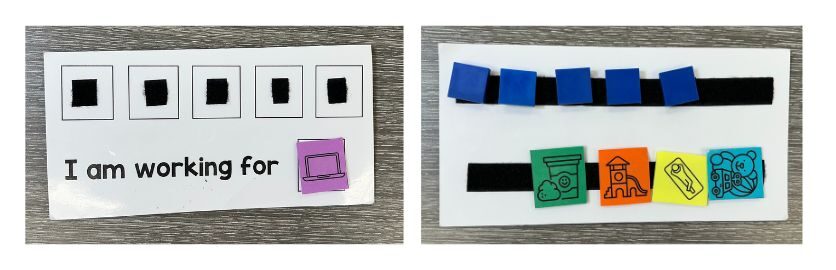

- Token chart: Sometimes, working for something tangible can be helpful. I like to use a token chart, which is pictured above. Students work for tokens, which are collected to earn a reward. Rewards can vary but might include a break on the playground, screen time, a tangible prize from a treasure box, etc. This can be scaled based on the child’s age and ability level.

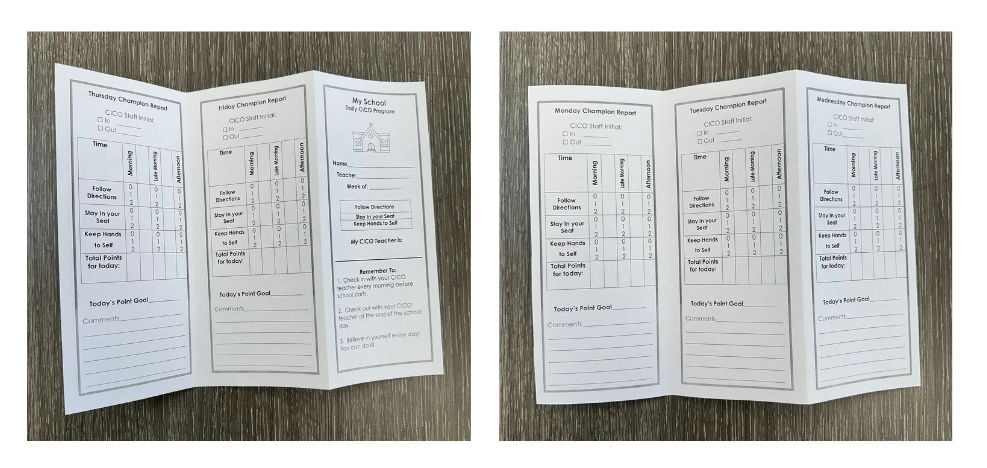

- Check-In/Check-Out: At my school, we lovingly call this “CICO” (key-co). Students check in at the beginning of the day with a trusted adult, someone who is not their teacher. This could be an administrator, your school secretary, another teacher, or even the custodian. Anybody they have a positive rapport with and can be available consistently is a great choice. The adult reviews agreed-upon expectations for the day and sets an attainable point goal. The classroom teacher awards points based on the expectations throughout the day. At the end of the day, the student goes back to check out with their CICO mentor. If their point goal for the day is met, they are rewarded with something that motivates the student. For some, that might be a tangible item. Others might want to throw a football back and forth with their mentor, play a game, or earn a small amount of screen time. We have seen this strategy be incredibly effective, even in its simplicity.

-

Here is an example of a CICO form used in my district. The goals and objectives should be customized based on the needs of each student. - Forced Choice: You may already do this, but this is a way to offer a child choice while maintaining boundaries. “You can work on this with a pencil or with a marker. Do you want to start with the first problem or the last problem? Let me know what you decide. For some students it is helpful to walk away while they make a decision. This allows them to work through their feelings for a few moments more privately and without an audience. Come back promptly and help them get started.

- Momentum Building: Get your students to do something they feel comfortable with before expecting compliance with a nonpreferred task or activity. This can often be achieved with humor or even with something as simple as singing “head, shoulders, knees and toes.” Once momentum is built up and the mood is lighter, they may be willing to follow along with what you are asking.

- Positive reinforcement: You are an amazing teacher, so you probably already do this… but it might be time to kick it up a notch. I like to have my entire class cheer for the students when they are making helpful choices. Usually, the kids take the cue and start a cheering squad for anyone and everyone. It’s so pure and genuine and a great time for all.

- Planned Ignoring: If the previous option isn’t successful, planned ignoring may be helpful. Take away the audience for whatever outburst is occurring. This might mean sending the rest of your class out of the room and letting the tantrum run its course. This also might mean allowing the child to elevate until they finally give up or give in. Yes, this could involve throwing things or being destructive. The child is likey trying to elevate to get you to give that attention back. That sounds really heavy and probably goes against your instincts, but it is sometimes necessary. As long as the child is safe, keep ignoring. If you have to intervene for safety reasons, intervene. Say, “I won’t let you do that,” and then keep ignoring. Do not engage or talk with the child during this time. Keep the corner of your eye on them and turn your body the other way if possible. Call for backup and stand your ground until the child begins to de-escalate.

- Tension Reduction: No matter what type of outburst you are experiencing, eventually the meltdown will run through an entire cycle and you will encounter the phase of “tension reduction”. That means the dysregulation needs to peak fully, and then the child will start to come down from an elevated state of emotion. Every person looks different in their state of tension reduction. Sometimes, it can be silence, a physical change in posture, crying (if it wasn’t happening during the elevation), or even falling asleep. You know your students, so you can likely identify when this happens easily. Once tension reduction has occurred, give the child a few extra minutes, and then you can begin the process of restoration or circling back to routine and expectations. Visit the Crisis Prevention Institute (CPI) website for more information and a free download on de-escalation tips.

- Documentation: Be sure to document the behaviors that occur. Take notes of what you are doing, what you have tried, and what works (or doesn’t). Keep your notes neutral and fact-based, or take tallied data for a specific target behavior. For example, Sally eloped three times in a 10-minute time period. This will help as you advocate for the student to receive support beyond your classroom walls.

If you are reading this, you are probably experiencing some challenges in your classroom or even in your home. Unfortunately, there is not a magic formula to any of this because we are working with human beings. Every individual will need unique help and support. Some things on this list may work one day and then the next they won’t. Not every strategy will be effective every time you try it, so take it day by day. Moment by moment, even! Defiant behaviors are an incredible challenge. The most important things are that the student is safe, the rest of your class is safe, and you take care of your health. Don’t downplay the challenge. Reach out to the resources your school offers, and don’t do this on your own!

Let me know in the comments below. What did I miss? Would you try any of these strategies in your classroom? What else is working for you these days? I can’t wait to hear from you.

-Kim

———————————-

Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to HeidiSongs Streaming Videos, and follow us on Instagram, Facebook & Pinterest! Check out our website at HeidiSongs.com, and find us on Teachers Pay Teachers right here.

Leave a Comment